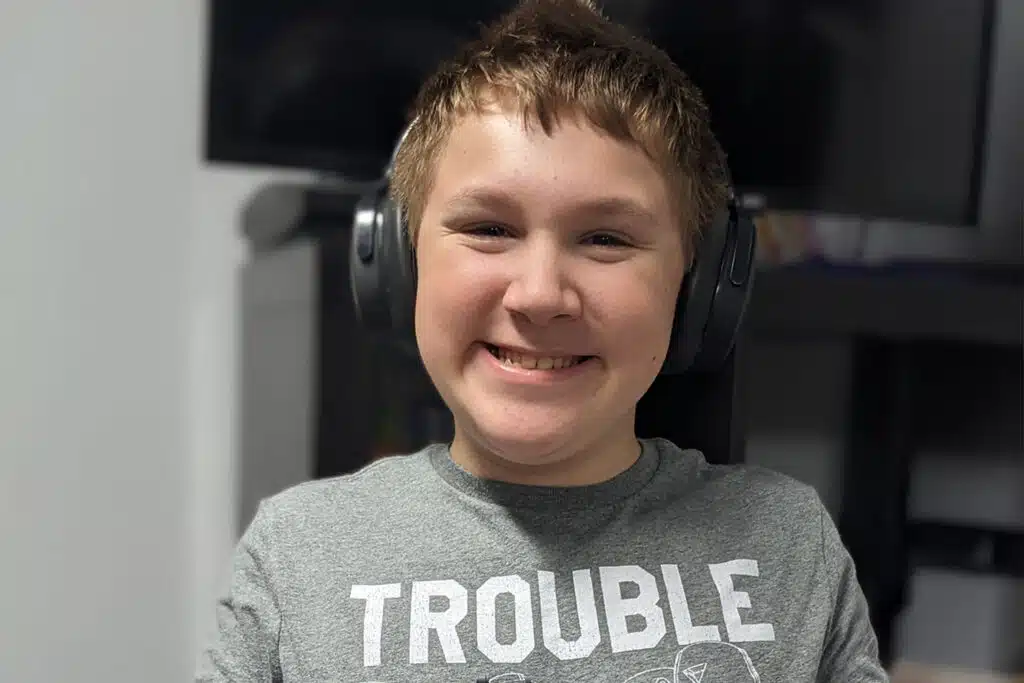

With the right support, kids like Coltrane can embrace their strengths

Thirteen-year-old Coltrane is creative, empathetic, and bursting with ideas, songs, and trivia. His mom, Jen, describes him as “super-duper-ultra-mega rare”—a one-of-a-kind gem. But as a toddler, Coltrane struggled to be understood. He had so much to say but wasn’t able to express it.

“It was heartbreaking,” Jen remembers. “I felt I was failing him as a parent because I couldn’t translate his sounds into words.”

After doctor visits and assessments, Coltrane was diagnosed with autism and apraxia of speech before he was four years old. His neurodiversity is a big part of what makes him who he is.

The term “neurodiversity” is intended to reduce stigma around developmental differences and acknowledge that there are natural variations in how brains work. The concept was introduced several decades ago (many attribute the term itself to Judy Singer, an Australian a sociologist on the autism spectrum).

The term “neurodiversity” is intended to reduce stigma around developmental differences and acknowledge that there are natural variations in how brains work.

This more nuanced perspective emphasizes the strengths of different ways of thinking and how to work within them, rather than treating them as problems. That shift is part of a larger, important conversation about how we support people with disabilities.

No one, least of all children, should feel defined by a diagnosis. Every child (and adult!) needs support to thrive; the types of support simply vary depending on circumstances and physical or psychological needs.

Differences are not defects. When we expand our ideas of what a “typical” child needs, we create environments where more children are valued and can access the tools they need to grow and discover their purpose.

There’s still a lot of work do be done to create equitable opportunities for children with disabilities. Government funding cannot cover all supports, and public health waitlists stretch for years. Especially as economic uncertainty increases, the cost of care is out of reach for many families.

When Coltrane started school, his government funding for therapy decreased. And Jen’s own health issues made working difficult.

“In times like these, people turn to their families and communities for support,” says Jen. She turned to fellow parents who also have neurodiverse children, and they suggested applying to Variety BC to fund Coltrane’s speech therapy.

With Variety’s help, Coltrane receives ongoing speech therapy, which has made a world of difference. “Within the first couple of years, his vocabulary expanded exponentially,” says Jen. Today, he can tell others about his passion for history, video games, and so much more.

Coltrane’s voice and perspective matter. And that’s why concepts like neurodiversity are vital. They push us to think beyond cookie-cutter definitions and welcome the astounding variation in the human experience.